INTRODUCTION

Newly qualified midwives (NQMs) are valuable individuals as they represent the progression of midwifery1. Hence, the ability of these NQMs to effectively make the transition from a student midwife to a registered midwife affects both the midwifery profession and maternity health services2. A smooth transition is a key aspect of job retention, especially since many countries worldwide fear the availability of an inadequate number of midwives for future staffing requirements3. In the published literature, NQMs describe their transition from student midwives to qualified midwives as a ‘reality shock’4,5 which could leave NQMs devastated and unable to process and express their emotions after facing traumatic experiences that could present either ‘too unexpectedly’ or else ‘too soon’, caused by various factors like experiencing abuse from staff members or when facing obstetric emergencies, possibly leading to secondary post-traumatic stress6. Such issues highlight the importance of making the transition of NQMs a time that helps them develop confidence and competence7.

To qualify as a midwife, one must undergo a midwifery education program that fulfills the academic recognition stipulated by their country, whereby most midwifery courses need to be completed within three to four years to attain a diploma or degree in midwifery studies8. Attaining the relevant academic midwifery qualification equips a NQM with the necessary knowledge and skills to care for women during normal pregnancies and assist them in childbirth. Moreover, a NQM is also expected to have the ability to detect complications in both the mother and infant, take preventative measures for these complications and carry out emergency measures for complications that may arise during pregnancy, childbirth, and the postpartum period9. An NQM should also have acquired the general knowledge and skills to provide counselling and education on women’s reproductive and sexual health and childcare to women and their families9. The international definition of a qualified midwife as stated by the International Confederation of Midwives (ICM)9 is: ‘A midwife is a person who has completed a midwifery education program that is based on the ICM Essential Competencies for Basic Midwifery Practice and the framework of the ICM Global Standards for Midwifery Education and is recognized in the country where it is located; who has acquired the requisite qualifications to be registered and/or legally licensed to practice midwifery and use the title ‘midwife’; and who demonstrates competency in the practice of midwifery’9.

The experience of childbirth is a particularly important and emotional event in a woman’s life; it will forever affect how she sees herself as a woman, and her relationship with her partner and other family members10. This highlights the importance of having NQMs who feel/are confident and competent while caring for women and that a midwife’s well-being has a direct impact on the care provided to a woman11. Therefore, an integrative review was undertaken to investigate what NQMs experience as they embark on their new professional role and care for women in the maternity setting.

METHODS

An integrative review (IR) method combines research and draws inferences from various sources on a topic by looking at and taking into consideration all literature present during the search, being empirical, methodological, and theoretical12. As Toronto and Remington12 suggest, for both transparency and rigorousness, this review was based on a systematic approach using Cooper’s 1984 framework12, which consists of a six-step process that was implemented as guidance. These six steps include: formulating the purpose for the review and formulating a review question; executing a systematic search; selecting appropriate literature; performing a quality appraisal of the literature chosen; carrying out analysis and synthesis of the studies; and discussion, conclusion, and dissemination of the findings12.

Formulating the review questions

The SPIDER method (Table 1) was utilized, this acronym helped to develop the review questions, create keywords, assist in listing both the inclusion and exclusion criteria (Table 2), and guide the literature search13. Both authors discussed and agreed on these elements for this IR.

Table 1

SPIDER method for developing keywords used for the literature search

Table 2

Inclusion and exclusion criteria used to select the studies for this review

Keywords (Table 1) were sought with the help of the medical subject heading (MeSH) database. Consequently, the following three review questions were formulated to help guide the literature search: ‘What are the experiences and feelings of NQMs when caring for women in the maternity setting?’, ‘What may influence the NQM experiences on the job?’, and ‘What strategies may enhance the NQM’s new role?’. Before commencing the literature search, the keywords were combined with the Boolean operators AND and OR, with an asterisk (*) used at the end of certain truncated words to search for all possible endings, and the use of the question mark (?) to replace or represent more than one letter14.

Systematic search and selection of literature

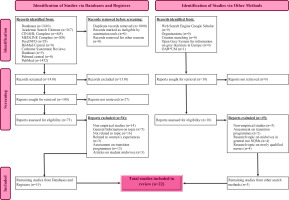

An extensive literature search was completed by the first author, between December 2021 and the end of July 2022 by combining the keywords presented in Table 1. The following eight databases were used to search the literature: Academic Search Ultimate, Cinahl Complete, Medline Complete, PSYch INFO, BioMed Central, Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, PubMed, PubMed Central, and the use of the Google Scholar search engine. All quantitative, qualitative, and mixed-method studies addressing the review questions, were considered for inclusion in this review. No limiters such as the location of keywords, full text, original articles, language, and sample were set during the main search. Limiters were not used since an initial quick literature search indicated that studies published on the topic were few. Hence, to avoid missing any important studies, all that was available was taken into consideration. This was also applicable for the time limit; since no relevant publications dating further back than the year 2000 were found, no time limit was set. Furthermore, the reference lists of the chosen articles were thoroughly scrutinized for any other relevant studies. The retrieved articles were retained according to the inclusion and exclusion criteria (Table 2) for this review. A total of 91 articles were retrieved in full text and, after applying the exclusion criteria, a total of 22 studies were retained for the review. Figure 1 displays the PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses) flow diagram showing the number of records identified, included, excluded, and the reasons for exclusion15.

Quality appraisal

To determine if the results of the study were valid and could be used for further research studies, education, policies, or clinical practice, an evaluation for utility and quality was done using appraisal tools. Table 3 shows the appraisal tools used for each study included in this review according to its research approach. Table 4 gives a summary of the final 22 studies used in this integrative review, showing the authors, year of publication, methodology, sample size and sampling, the participants, and the data collection methods used. It also indicates the region/country where the study was done, giving a cultural context perspective that could reflect cultural implications in the results. The studies were appraised by the first author, and the processes were reviewed by the second author. The outcomes were discussed and agreed upon by both authors.

Table 3

The three tools used to appraise the different research approaches of each study

| Research approach | Studies | Appraisal tool |

|---|---|---|

| Qualitative studies | Avis et al.29 Barry et al.19 Barry et al.1 Cazzini et al.24 Clements et al.2 Fenwick et al.34 Griffiths et al.21 Hobbs22 Kitson Reynolds et al.20 Kool et al.25 Naqshbandi et al.27 Norris28 Saliba31 Sheehy et al.8 Simane-Netshisaulu and Maputle33 Skirton et al.26 van der Putten5 Wain4 Watson and Brown23 Young35 | The Critical Appraisal Program (CASP) qualitative studies tool |

| Quantitative studies | Davis et al.37 | Critical Appraisal of a Cross-sectional Study (Survey) from the Centre for Evidencebased Management (CEBMa) |

| Mixed-method studies | Lennox et al.30 | Mixed-Methods Appraisal Tool (MMAT) |

Table 4

Summary of literature included in the review

| Authors Year | Location | Methodology | Sample size | Sample technique | Participants | Data collection |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cazzini et al.24 2022 | Republic of Ireland | Qualitative study | 7 | Convenience sampling | NQMs who had commenced their post registration clinical practice in a large teaching hospital | Semi-structured interviews |

| Simane-Netshisaulu and Maputle33 2021 | South Africa | Qualitative study | 5 | Non probability purposive sampling | NQMs working in selected maternity units during their first year from completion of training | Unstructured in-depth interviews |

| Sheehy et al.8 2021 | Australia | Qualitative study | 28 | Non probability sampling | Re-recruited participants from a previous longitudinal study | Semi-structured telephone interviews |

| Watson and Brown23 2021 | Northern Ireland | Qualitative study | 8 | Purposive sampling | NQMs who had obtained their registration in the last 12 months and taken a post with Health and Social Care trust | Semi-structured in-depth interview |

| Kool et al.25 2020 | Netherlands | Qualitative study | 21 | Snowball sampling | NQMs graduated less than 3 years ago and work as hospital-based midwives in Netherlands | Interviews |

| Naqshbandi et al.27 2019 | Erbil Iraqi | Qualitative study | 15 | Convenience sampling | NQMs who were in their transition period | Semi-structured in-depth interview |

| Norris28 2019 | United Kingdom | Qualitative study | 5 | Convenience sample | NQMs in a maternity unit | Focus groups and reflective diary |

| Griffiths et al.21 2019 | Australia Queensland | Qualitative study | 8 | Purposive sampling | Midwives who had just completed their BMid as part of the RPMEP | Semi-structured telephone interviews |

| Wain4 2017 | United Kingdom | Qualitative study | 8 | Purposive sampling | NQMs who had completed their preceptorship | Semi-structured interviews |

| Kitson Reynolds et al.20 2014 | United Kingdom | Qualitative study | 12 | Cohort sampling | NQMs during their first year of practice | Semi-structured interviews |

| Barry et al.1 2014 | Perth Western Australia | Qualitative study | 11 | Purposive sampling | NQMs who were previously nurses | Interviews and participants journal |

| Barry et al.19 2013 | Perth Western Australia | Qualitative study | 11 | Purposive sampling | NQMs recruited on their last day as student midwives | Semi-structured interviews and researcher field notes |

| Clement et al.2 2013 | Australia | Qualitative study | 38 | Purposive sampling | NQMs recruited from 14 public maternity hospitals | Telephone interviews and focus groups |

| Lennox et al.30 2012 | New Zealand | Mixed-methods study | 8 | Purposive sampling | NQMs who had just been registered as midwives | Semi-structured interviews and telephone logs |

| Davis et al.37 2012 | Australia | Survey | 25 | Convenience sample | All NQMs employed within three participating Area Health Services | Surveys |

| Avis et al.29 2012 | United Kingdom | Qualitative study | 35 | Convenience sample | NQMs from 18 work sites | Diary and interviews |

| Young35 2012 | United Kingdom | Qualitative study | 36 student midwives 5 midwives 12 mentors | Convenience sampling | Student participants were recruited from the 3-year Preregistration Midwifery | Focus groups, observations and interviews |

| Hobbs22 2012 | United Kingdom | Qualitative study | 7 | Non-probability sample | NQMs working in the major maternity department | Observations, interviews and personal field diary |

| Skirton et al.26 2012 | UK | Qualitative study | 35 | Purposive sampling | Final year midwifery students | Diary |

| Fenwick et al.34 2012 | Australia | Qualitative study | 16 | Convenience sampling | Newly qualified midwives who were participants in a longitudinal project | Interviews |

| Saliba31 2011 | Malta | Qualitative study | 11 | Purposive sampling | Newly qualified midwives who had just started their employment at Mater Dei Hospital | Interviews |

| van der Putten5 2008 | Ireland | Qualitative study | 6 | Purposive sampling | Newly qualified midwives who qualified in the last 6 months | Interviews |

Analysis and synthesis

To get a better understanding of the topic, comprehensive methods of data analysis were implemented for this IR, which allowed recasting, combining, reorganizing, and integrating concepts across a body of literature16. Data analysis was conducted by deconstructing the articles into their simplest elements17. To efficiently analyze the articles, three review matrices were constructed, each representing a review question12. The three analysis-matrices used in this review were thoroughly scrutinized for recurrent patterns, and the formation of themes was guided by the review questions12. These processes were done by the first author under the supervision of the second author. Both authors discussed and agreed on the findings. Using the Braun and Clarke18 six-phase process helped to identify the following three themes: Shocking truth, Beginner’s crisis, and Moving on. This process included familiarizing with data where the article was read multiple times and notes were listed as codes for potential themes; generating initial codes, the data formed from the previous coding was organized into interesting codes; searching for themes, the codes were placed into potential themes and subthemes; reviewing themes where themes were refined by gathering items for each theme and a thematic map was developed (Table 5); defining and naming themes, the aspects of the data each theme captured were determined, and the story of each theme was studied to develop the final theme names; and producing the report where a report of the identified themes was developed.

Table 5

Thematic content map showing the process of developing the 1st and 2nd level coding, forming the subthemes and finally the three main themes

RESULTS

Emergent themes

Shocking truth

This theme brings out the stark realities NQMs experience when transitioning from the role of student to that of a registered midwife by looking at NQMs’ perceptions of what midwifery entails and their views of their real job experiences. This theme represents the research question, ‘What may influence the NQM experiences on the job?’. NQMs expressed a feeling of coming into the workforce proud of their graduation and achievements, and embracing the philosophy of midwifery19. In one study, this philosophy of midwifery referred to the combination of learned theory, accumulated clinical practice during studentship, and individual experiences of childbirth19. NQMs had an idea of what a midwife is, what the job involves, and the relationships they will build with their colleagues, the women they care for, and their families20-23. However, this changed over time, once they embarked on the journey of truly becoming a midwife20. Participants in many studies experienced a huge surprise when they started practicing in a professional setting, encountering many unexpected scenarios, from what they had been taught and their views on maternity care, to what was practiced in the clinical setting. Leading to a sense of frustration when they could not reach their expectations of their midwifery role19.

It emerged that the working environment is based on a medical setting where certain unneeded interventions take place, which led to NQMs looking at the midwifery role as being subordinate8. NQMs indicated that the clinical placement could not compare to the midwifery philosophy they believed in24. One study particularly showed that the initial feelings of NQMs as they cared for women, were of ‘letting women down’19 and not giving them the support, standard of care, and attention, they had envisioned19,20. NQMs felt that they were not able to provide proper woman-centered care as they had intended5,20,21,25,26, leading to NQMs feeling guilty when they did not dare to speak up for women and stand up to other staff members when they felt that women were not receiving proper care24.

However, this could be based on the environment these NQMs were exposed to since in two studies, NQMs had the opportunity to work in caseload midwifery practice. This included student midwives caring for an assigned woman throughout pregnancy, birth, and the postnatal period. This resulted in these NQMs experiencing a completely different aspect of the job description once they were employed as midwives in a hospital-based maternity setting. This is one of the reasons that NQMs became disappointed after having different expectations from the role20,21. Whereas NQMs who worked their transition period within the midwifery continuity of care model regarded their experience as a positive one, describing it as having the opportunity to work closely with other midwives, sharing the same philosophy of care, and keeping women at the center of care. In contrast, those from the same study who were assigned to a hospital-based setting expressed negative feedback about their experience2.

Beginners’ crisis

This theme highlights the difficulties found across the literature that NQMs experience in their new role as registered midwives in a maternity setting. This theme represents the research question: ‘What are the experiences and feelings of NQMs when caring for women in the maternity setting?’. Literature indicates that it is quite common for NQMs to experience a surge of feelings and emotions, which may contribute to a lack of confidence and mediocre performance, making them vulnerable persons during an exceedingly difficult and stressful time of their professional career8,27,28. All included studies (n=22) revealed that NQMs experienced some form of stress, with two studies indicating that stress was linked to the phenomenon of sudden status change; from being a protected student to becoming a fully independent and accountable midwife4,20. The feeling of losing the shelter provided by their university20, stepping into the unknown29 and starting to find out the true demands of midwifery was all about experiencing the reality of both sides of the profession, from happy/joyful moments to sad, heartbreaking situations30. NQMs revealed that they did not realize the responsibility of being a midwife while they were students and, therefore, found it stressful once they were employed in their new role, taking sole responsibility and decision-making for the women under their care26. Three studies show that this sense of responsibility was seen as overwhelming by the participants5,23,31.

Studies revealed the steep learning curve that was expected by employers, where NQMs were expected to increase their knowledge regarding certain skills and practices for which they had not been previously trained8,22. NQMs were mostly worried about being those who must act during emergencies without any shielding23. As students, NQMs never took decisions on their own while caring for women during labor while, once qualified, they were afraid of the heavy responsibility and that they would make a mistake that would cost them their registration2. Furthermore, participants put themselves under intense pressure due to increased expectations of their abilities to carry out tasks at the same pace as their senior counterparts22. This led to deep frustration, knowing that their ability to transition into their new role would be much slower than they anticipated32. Such issues surfaced mostly in birthing units, especially during vaginal examinations (VEs), the second stage of labor, and when interpreting cardiotocography (CTG) results22,25.

Participants felt that even though they were educated and trained on responsibility, accountability, and autonomy as students, they did not feel up to these in their first 12 months of employment20. NQMs went through so many conflicting ideologies when they tried to use the knowledge they acquired from school into practice, that it resulted in impeding their self-confidence5,23,27. Although studies mention that NQMs were conscious of their abilities in knowledge and skills, they mostly felt that their position as an NQM was subordinate, and this unfavorably affected their ability to be sufficiently assertive to deal with the events and tasks presented to them. NQMs described the role of the midwife as intense and emotionally demanding, while not finding the right support from colleagues, which proved to have a negative effect8,32. One study compared being accepted by senior midwives to an ‘initiation period’20, meaning that they felt as if they had to pass a test to be accepted by their senior counterparts. Other NQMs described their struggle to be accepted by other midwives as a challenge that had to be endured28. NQMs felt continuously watched by colleagues, waiting to be judged on whether they stepped out of line and whether they can be trusted2,21. They felt that they were mostly seen as a burden, lacking skills, ability, and competence8,21,23,24,30. Studies by Kool et al.25, Norris28and Wain4 have all described the dilemmas NQMs face when they need to ask for help from other midwives or refer women to obstetricians. Fearing that they would be seen as weak and incompetent, NQMs felt like a nuisance to ask for help/support, especially in busy environments and short-staffed circumstances, shattering their hopes of building a trusting relationship with colleagues24,26. Sheehy et al.8 and Simane-Netshisaulu and Maputle33 describe a bullying culture where NQMs feel belittled by a hierarchical system and autocratic personalities. This is also shown in the studies of Fenwick et al.34 and Lennox et al.30 where a pattern of inappropriate working culture was noted in some units, where midwives rank themselves according to seniority with NQMs placed at the bottom of the hierarchy, the well known ‘pecking order’30.

Findings of one study revealed how participants felt helpless and did not know what to do to perform their role, with one of the participants expressing that she felt ‘like a fraud’30 while speaking to a mother who was continuously thinking that this woman should be speaking to ‘a real midwife’30 . On the other hand, in another study, a common expression by NQMs was ‘fake it till you make it’8, which involved mimicking skills from other colleagues even though they were not aware of what they were doing8.

Most NQMs take all these fears, feelings, and emotions back to their own homes, worrying that they failed as midwives and believing that they did something wrong while caring for women20,25. Worst of all, they even compared themselves to others, which, eventually, may take a toll on their personal lives. Participants complained of not being able to sleep and constantly counting the days until their next duty28. Others commented on not taking any breaks during their duty or staying on after their duty ended, to see the outcome of the birth even though they were exhausted and needed to go home to their families22,23. Their coping skills and anxiety were based on how and if they would manage to complete the tasks assigned to them28. Such findings also emerged from a study22 focusing on Bourdieu’s notion of habitus, which is defined as ‘our overall orientation to or way of being in the world; our predisposed ways of thinking, acting, and moving in and through the social environment’22 . Hence, Hobbs22 explains that NQMs tend to overlook their wellbeing since midwifery is a female-dominated profession and it is in their nature to give their 100% and more, which Bourdieu refers to as ‘service and sacrifice’22.

Six of the studies included in this review2,4,8,25,29,34 presented the experiences of NQMs when working on a rotation basis. This brought about instability in their confidence8, insecurity, and having to prove themselves to colleagues in an extremely limited period24,25. Time is needed in one clinical area to consolidate and gain knowledge and experience4. However, some conflicting ideas emerged between participants, such as in the study by Avis et al.29 where some participants agreed with the negative effects of the rotation system, describing it as a ‘roller coaster ride’, while others described it as building their confidence since they had the opportunity to witness various scenarios from different ward settings. Similarly, in Clements et al.2, participants working in the continuity of midwifery care setting did not experience any feelings of stress, fear, or anxiety during their rotation. However, the findings of these studies could have been affected by organizational structures and dimensions, the geolocation of the studies, and personal character traits. Workload and time constraints were other factors that made it extremely difficult and stressful for NQMs to provide proper care and attention to women during labour25. Moreover, the inability to provide proper woman-centered care was yet another added concern for NQMs when assigned to shifts, as it made them feel that they lacked continuity of care21. However, these participants had been given their midwifery training in a caseload midwifery setting, which differs from a hospital-based maternity setting, and hence, their feelings might have been accentuated by this fact21.

Moving on

The final theme in this review investigates several factors that NQMs identified as helping them accept, adapt, and move forward in their new role, representing the final research question: ‘What strategies may enhance the NQM in her new role?’. Over time, participants started to feel more confident, obtained a clearer picture of what was expected of them28 and were able to put their knowledge into practice26,31. One study explains that NQMs go through three stages while transitioning from students to qualified midwives to provide woman-centered care1. These three stages include: being centered on developing their personal qualities, developing an understanding of outside influences that may impact their practice, and moving through a process to support change through their plan of action1. The feeling of belonging to the profession and their role as a midwife helped NQMs not only to provide the best care to mothers but also set boundaries to help themselves survive. These included working autonomously, gaining professional recognition, respecting their family commitments, and supporting their emotional demands1. Other factors that encouraged NQMs to retain their profession, and achieve job satisfaction and motivation were the ability to work within the full scope of midwifery practice and building a good relationship with the women in their care8,25. Receiving positive feedback and trust from the women they cared for was considered an important job resource, which instilled a feeling of empowerment in new midwives19.

Another factor that helped NQMs cope with their transition, was being assigned to work in clinical areas where they previously trained as students helping them to adapt faster in their role due to the familiarity with the ward setting and workforce8,24,31. It also helped them in the steep learning curve and to provide better care to women8,24,31.

Additionally, two studies point out that the structure of clinical placements previously familiar to student midwives directly influences NQMs once they start to work21,26. Hence, being oriented with the clinical setting and equipment30, whilst being informed about ward/hospital protocols and guidelines, gave NQMs a feeling of security, knowing what is expected of them in the early days of their employment8,29. Likewise, organizational structures within the hospital helped NQMs to work to the full scope of the midwifery practice8.

Five studies show that when NQMs were supervised or assigned to a senior midwife, facilitator or preceptor during duties, NQMs’ confidence increased, giving them a sense of security4,24,25,29,31 emphasizing that being surrounded by support from colleagues was deemed crucial and helpful23-25,29,31. Naqshbandi et al.27 add that supportive colleagues help NQMs to adapt faster, have a smooth transition, increase confidence, and make them more likely to retain their profession. This support offered NQMs positive learning experiences in practice8,28 and helped with stress and anxiety24. Fitting in and feeling accepted and not judged was an inspirational goal for NQMs28,34. NQMs also expressed that being in the company of colleagues during duties and breaks, team building activities and socializing during out of duty hours were all assets in building relationships and enhancing their work practice8,24,25.

NQMs’ decision-making skills were developed when they were assigned to another colleague and were given the possibility to speak about their concerns35. Moreover, decision-making skills were also improved when senior midwives dedicated time to explain and discuss with NQMs the rationale behind a decision rather than leaving them to fend on their own35 or taking over their work30. Senior midwives must become aware that their positive support encourages NQMs to remain in employment27, especially with the increasing concern of the availability of an insufficient number of midwives for future staffing3.

Apart from being supported, debriefing was also found to be vital for NQMs to survive and move on in their midwifery role8. Participants explained that having the space to vent their feelings about their experiences and challenges, helped them to relieve their anxiety, learn, and progress8,30. Furthermore, having a friend who is going through the same experience also helped in relieving anxiety23,24. Additionally, having the possibility of assigning NQMs to a one-to-one woman-care ratio during the first few months of work is deemed to be a beneficial consideration4. Being placed in a shift that is made up of mixed levels of staffing experience8 and is considered supernumerary23,24 was also seen as an important strategy for learning and safety in practice.

Another factor found to enhance the transition phase of NQMs was having good organizational support, which was shown to be an asset for NQMs. This support translates to having sound induction programs allowing NQMs to orient themselves with units and equipment30, be introduced to policies and guidelines8,29, be assigned to preceptors, have supervision, and be assigned over and above the staff requirement of the clinical area8,23. These provided NQMs with a smooth transition into the workforce. The organization should endeavor to support and empower NQMs to further their studies to allow them to expand their knowledge, and stay up-to-date with the latest evidence-based literature, besides keeping them motivated and giving them a sense of belonging25. Feeling appreciated and being acknowledged by the system as a contributing professional was perceived positively by NQMs8.

DISCUSSION

This review aimed to explore the experiences of NQMs when caring for women in the maternity setting. The literature demonstrated how NQMs’ wellbeing is at stake after registration, as they go through a tumultuous period full of psychological stress, fear, and other surges of negative emotions since the role of the midwife is very intense and emotionally demanding8. This difficult period is linked to the new responsibilities of their role, especially when it comes to decision-making, which may influence their confidence and competency20. The sudden change of role to a more demanding and responsible one might come to what was explained by Kramer in 19744,5, as a ‘reality shock’, where what was expected and envisioned as students becomes shattered once they join the workforce20-22. Participants felt helpless in the early days of their professional role as they did not have the understanding or the experience to perform their roles effectively and efficiently30. Feelings of incompetence and lack of self-confidence had an increased influence on the stress levels of NQMs, causing a psychological impact on them since they had become the sole-accountable person for the mother and baby under their care. Most were afraid to assume this newly acquired responsibility out of fear of making a serious mistake, which would cost them their midwifery licence2. All these emotions, together with lofty expectations and the lack of support from colleagues, were taking a toll on their personal lives, which could lead to compassion fatigue, which is known as the ‘cost of caring’6, especially when exposed to obstetric emergencies, leading to less compassion satisfaction36. These emotions were mostly dependent on the different settings NQMs were enrolled in since participants felt less psychologically affected and more at ease when they were not assigned to birthing units in a hospital-based setting but worked in caseload midwifery practice2.

Most of the literature reviewed also highlights the transition phase from being a student to becoming a midwife1,2,4,8,19-25,27,28,30,31,34,35,37. The findings from the studies concur with a three-phase gradual transition where, primarily, NQMs felt the loss of what was familiar to them; teachers, school colleagues, mentors, and the shelter provided by their university20, whilst stepping into a whole new world and a role of uncertainty29. This IR also showed the importance for NQMs to form new and trusting relationships with colleagues and women patients, trying to fit in and carry out the necessary skills needed to perform tasks. Finally, it became evident that as time passed, participants were finally reaching the stage where they wanted to be, in the ‘promised land’28 . In this new phase of adaptation, although still scary and risky, NQMs now feel they have a clearer vision of what is expected of them28 and start to apply all the knowledge they already possess with that they continue to acquire from their new experiences1. They are ready to let go of what passed and try to adapt to their new role and environment as more autonomous midwives28, leading to job satisfaction where they feel they are finally truly helping women8,25. Senior midwives were found to play one of the biggest roles in guiding and helping NQMs succeed25,29,31. When senior midwives were readily available to explain, guide, and help without any form of judgment or exercise of superiority, this was the ideal situation for NQMs to learn and advance in their practice2,21,25,27,29,31. Kitson Reynolds20 and Cazzini et al.24 emphasized the importance of giving NQMs time and space for debriefing and considered this to be instrumental for all healthcare professionals. Debriefing should not only be available after an emergency or traumatic experience but for anyone who needs it20.

CONCLUSIONS

Transitioning from a student to a midwife brings about stress and tension, especially as NQMs take full responsibility for the women under their care, knowing that their decisions can have a direct impact on the outcome for women, newborns, and families. Literature shows that the factors that influence NQMs include the working environment, especially when working in birthing units, the support given by colleagues, and the organization in which they are employed. It is therefore very important that NQMs find the needed support to be able to overcome this trauma before it is aggravated and leads to secondary post-traumatic stress. NQMs are a precious entity in healthcare, as they are the future of midwifery. Yet, research is still extremely limited, and, to date, the focus has mostly been on the transition to practice and on supportive programs such as preceptorship. Further research focusing on more holistic experiences of NQMs is warranted to enable a deeper understanding of their professional development.